Should you make your Thanksgiving meal healthier?

I believe that every body can enjoy a traditional Thanksgiving meal.

But as a nutrition student back in 2012, I would have found that statement reckless, disregarding the “epidemic” of weight/health challenges facing our country.

That year my parents traveled from Maryland to Denver to spend the Thanksgiving holiday with me and my family. While I swung kettlebells and climbed revolving stairs at 24 Hour Fitness, Mom and Dad went for a stroll around the neighborhood. While I ate a “lighter” lunch to “earn” and “burn” the calories I would consume, they ate their regular meals.

To me healthy meant I had to be thin, low body fat. Though far leaner in my mid-40s than I’d been in my 20s, I still didn’t like what I saw in the mirror. All I saw were my perceived flaws: the cellulite, my furrowed forehead and a roundness to my female belly that I believed wasn’t flat enough.

I cooked my family a “clean” holiday meal, removing ingredients that my nutrition books touted as “bad” — the marshmallows in my husband’s favorite sweet potato casserole, the gluten in my dad’s famous sausage stuffing.

But I wasn’t done subjecting my parents to my righteous rules of nutrition perfection. For a class project they agreed to track their food so I could scrutinize their supposed nutritional flagrancies and offer upgrades promising “better” health. Bless their hearts.

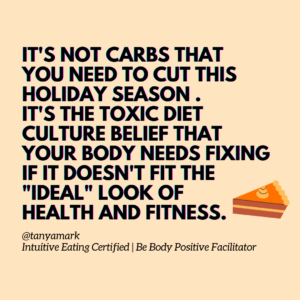

A diet-culture-laden decision

Looking back now, I see that neither my parents’ nutrition nor health needed fixing.

The real flaw?

My misguided belief in diet culture, disguised as wellness, and its simplistic, one-dimensional definition of health: that only a thin body is ideal. When we expose the origin of this false depiction of health and redefine it, every body can enjoy holiday favorites, no “earning” or “burning” of food required.

Weight doesn’t automatically equal health

According to Emily Nagoski and Amelia Nagoski, authors of Burnout: The Secret to Unlocking the Stress Cycle, “you’ve been lied to about the relationship between weight and health so that you’ll perpetually try to change your weight.”

This message is driven by what the Nagoski sisters call the Bikini Industrial Complex, the “$100 billion cluster of businesses that profit by setting an unachievable ‘aspirational ideal,’ convincing us that we can and should — indeed, we must — conform with the ideal, and then selling us ineffective but plausible strategies for achieving that ideal.”

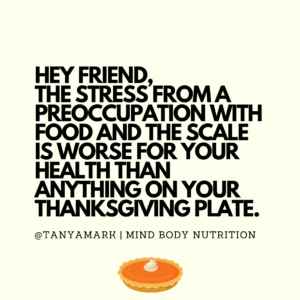

And sadly, this false and simplistic definition of “wellness” can lead to lifelong weight worry and make it difficult to feel good in our bodies. Simply put, it’s a chronic stressor.

Food psychologist Paul Rozin agrees. Evelyn Tribole and Elyse Resch, registered dietitians and authors of “Intuitive Eating,” say that in his 1999 research study “Rozin was way ahead of his time and concluded that the negative impact of worry and stress over healthy eating may have a more profound effect on health than the actual food consumed.”

Furthermore, Rozin’s research showed that while Americans have the most food worry and least food pleasure, the French were found to have the exact opposite, plus a longer life expectancy. Consider some mainstays of the French diet: bread, brie, creme brûlée — foods containing the “forbidden” ingredients my nutrition books said were “unhealthy.”

Yes, absolutely, nutrition plays a key role in your health and in preventing chronic disease, but your health is impacted by far more factors than nutrition and exercise. According to research in author Christy Harrison’s book “Anti-Diet,” “eating and physical activity combined account for only about 10 percent of population health outcomes.”

Yes, read that again.

Your health is complex

Other important factors include financial and social status, healthy childhood development, social environments, personal coping skills, traumatic experiences, weight stigma, access to health services, gender, race, physical environment, education and literacy, food and job security, and genetics.

And do you know what’s highly protective of your health?

Positive, satisfying relationships of any kind.

The Nagoski sisters found that relationship quality was a “better predictor of health than smoking, and smoking is among the strongest predictors of ill health.”

So this holiday season, instead of fretting over the marshmallows in your husband’s childhood favorite sweet potato casserole or the gluten in your father’s famous sausage stuffing, consider taking a gentle nutrition approach to healthy eating.

And let me be clear, if you enjoy making a healthier Thanksgiving meal and participating in the 5K Turkey Trot because they make you feel good, GO FOR IT!

Ultimately, remember that gentle nutrition, Principle 10 of Intuitive Eating, is about honoring your whole health.

Make an empowering decision

So taking all this into consideration, I’ll let you decide if you’d like to make your Thanksgiving meal healthier. Think about what might be healthiest for you.

But let’s not make it a “should.”

As a nutrition professional practicing gentle nutrition throughout the year, this year I’m choosing to enjoy a traditional meal. And, because I love moving my body, I’ll most likely hit the gym, not to “earn or burn” my food, but because it’s just what makes me feel strong and vibrant, period.

Happy Thanksgiving. ♡ Tanya

P.S. If you want to learn more, check out my article: Healthy eating doesn’t mean perfect eating.

P.S.S. This article is an edited version of the original published in the Jackson Hole News and Guide on November 25, 2020.